The economic policy of the 4th of August regime

In 1936, the Greek economy was in a precarious state, running a budget deficit of 844 million drachmas and dependent on a constant stream of ever-growing foreign loans.

The rate of unemployment in the country was high: in a country of about five million people, 135,000 were unemployed. In the port cities, a years-long recession had led to growing disaffection with the political world in Athens. In the countryside, legions of farmers faced ruin at the hands of loan sharks. Additionally, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Greek refugees from Asia Minor, uprooted after the war of 1920-22, were still living in hovels.

The parlous state of the economy was also the result of a laissez-faire approach to economy, a mismanagement performed by both Liberals and Populists prior to the Metaxas dictatorship.

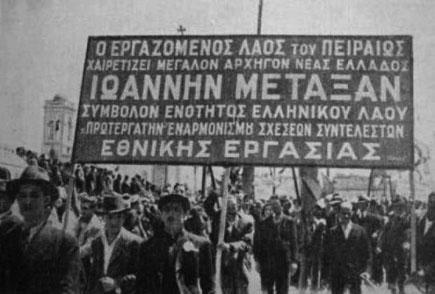

When Metaxas assumed power in 1936, the Greek government began to take a more active role in the economy. Under his dictatorship, new agricultural programs were launched, industrial outputs increased, new businesses were founded, Greek shipping profits reached a record high, higher taxes were collected from the wealthy to establish a welfare system and to support a future war effort, and Greece’s infrastructure was improved.

Metaxas established the Social Insurance Fund (IKA) in 1936, and its services were available throughout Greece by 1938. New labor reforms were implemented, such as the institution of union contracts, an unemployment insurance, maternity leave, the 5-day workweek, the 8-hours workday, holidays with full pay (guaranteed two-week vacations with pay or two weeks’ double pay in place of the vacation), stricter work safety standards, introduction of a minimum wage, mandatory paid leaves, banning child labour and building child care centres, regulations on rotatory work by shifts, new restrictions on the employer’s right to fire employees, the creation of new protected professions and the creation of a public employment agency. At the same time, corporate and luxury taxes raised.

While some historians claim that Metaxas rolled out these measures only to defuse social tensions, to placate simmering unrest and to avoid mobilizations against the regime, the fact remains that they improved the standards of the Greek working class. And it was well aligned with Metaxas’ ideology, since he had no love for the moneyed class. In a 1937 speech in the town of Ioannina he lambasted the rich as “a few thousand people… sitting in Athens making all the social, economic and political decisions, sucking Greece dry without giving anything back”. However, these reforms came with a price – repressive measures were taken and strikes were outlawed.

The regime was also able to stabilize the drachma, which had been suffering from high inflation. Exploiting the newfound solidity of the currency, the Metaxas government launched in April 1937 a 10-year program to help modernize Greece and embarked on large public works initiatives, including land drainage, construction of railways, road improvements, and updating the telecommunications infrastructure all across Greece.

Special care was shown by the Regime in regards to agriculture, especially on the matter of production. When Metaxas assumed power in August 1936, Greece’s imports greatly exceeded its exports. To lessen Greece’s dependency on food imports, Metaxas provided price support for certain agricultural products through the Central Committee for the Protection of Domestic Wheat Production (KEPES) and declared a moratorium on certain agricultural debts. Both measures raised incomes for the peasants. At the same time, in 1938 a ministry of Cooperatives was established to direct a new model of agricultural organization from above.

Farmers had their debts slashed and became entitled to buy out their tenancies with soft state loans, while full property title deeds were also given to refugee farmers for the land they were cultivating. Intensive cultivation was also promoted. Irrigation and drainage projects added thousands of acres for growing crops. The farm reforms helped wheat production to rise from 531,000 tonnes in 1936 to 983,000 tonnes in 1938. By 1939, Greece was producing enough wheat to meet 60% of domestic consumption needs. Cotton and tobacco production also grew significantly, while exports of olives, olive oil and tobacco soared.

The reforms worked out very well. Exports in 1938 rose by more than 57% per cent over the previous year. Currency reserves grew and the Athens Stock Exchange was consistently bullish. Greece’s merchant shipping tonnage in 1938 hit 1.87 million tons, making Greece the world’s 9th biggest commercial maritime power.

Greece’s industrial output increased a staggering 179% and production of electricity increased too. Furthermore, the workforce grew considerably, with construction, transport, agriculture, the textile industry, and engineering employing the largest numbers of workers. Over the first two years, the overall economic activity grew a stunning 138%, with a marked rise in per capita income.

As consequence of the better economic performance, unemployement, which was one of the regime’s primary goals, declined starkly. According to the German Embassy, during the first two years of Metaxas’ government the number of unemployed workers had been pushed down to 26,000 from 128,000 in 1936, and by 1939 the number had been drowned to just 15.000. (Pelt 2002, p. 156).

The armament industry also boomed, becoming Greece’s biggest industry and second largest export after tobacco in the late 1930s. The sales, especially for the Spanish Civil War needs, helped to improve the Greek economy and the success of Greece’s rearmament program, both objectives of the Metaxas regime. Anticipating a European war, the Greek government desired both a stronger economy and a modernized military.

Because of the high demand of weapons in the Spanish conflict, the Greek Government and the GPCC were able to sell munitions at inflated prices and make a substantial profit. The revitalized economy and the increased local availability of arms and ammunition as a result of the sales to Spain made the Greek rearmament program possible.

In fact, after 1939 a significant part of the national revenue was used for the purpose of rearmament, preparing defensively the country for the looming threat of WW2. The improvements in national security due to the modernization and strengthening of the Greek military were later demonstrated during the Greco-Italian War of 1940–1941, when Greece defeated Italy.

– By Andreas Markessinis

Mention: » The Ideology of the Metaxas Regime | METAXAS PROJECT | Ioannis (John) Metaxas

Mention: » Metaxas, Women, and the Nation | METAXAS PROJECT | Ioannis (John) Metaxas

Mention: » Archaeology under Metaxas | METAXAS PROJECT | Ioannis (John) Metaxas

Mention: The subjection of technology and science to the ideals of faith, will and the national ‘soul’ in the Metaxas regime | Metaxas Project